'The social and economic evils in our world are all too real – as is the need to make globalisation work for all the peoples of the world, by embedding the new global economy in a global society,

based on shared global values of solidarity, social justice, and human rights.' - Kofi Annan Source

Issue

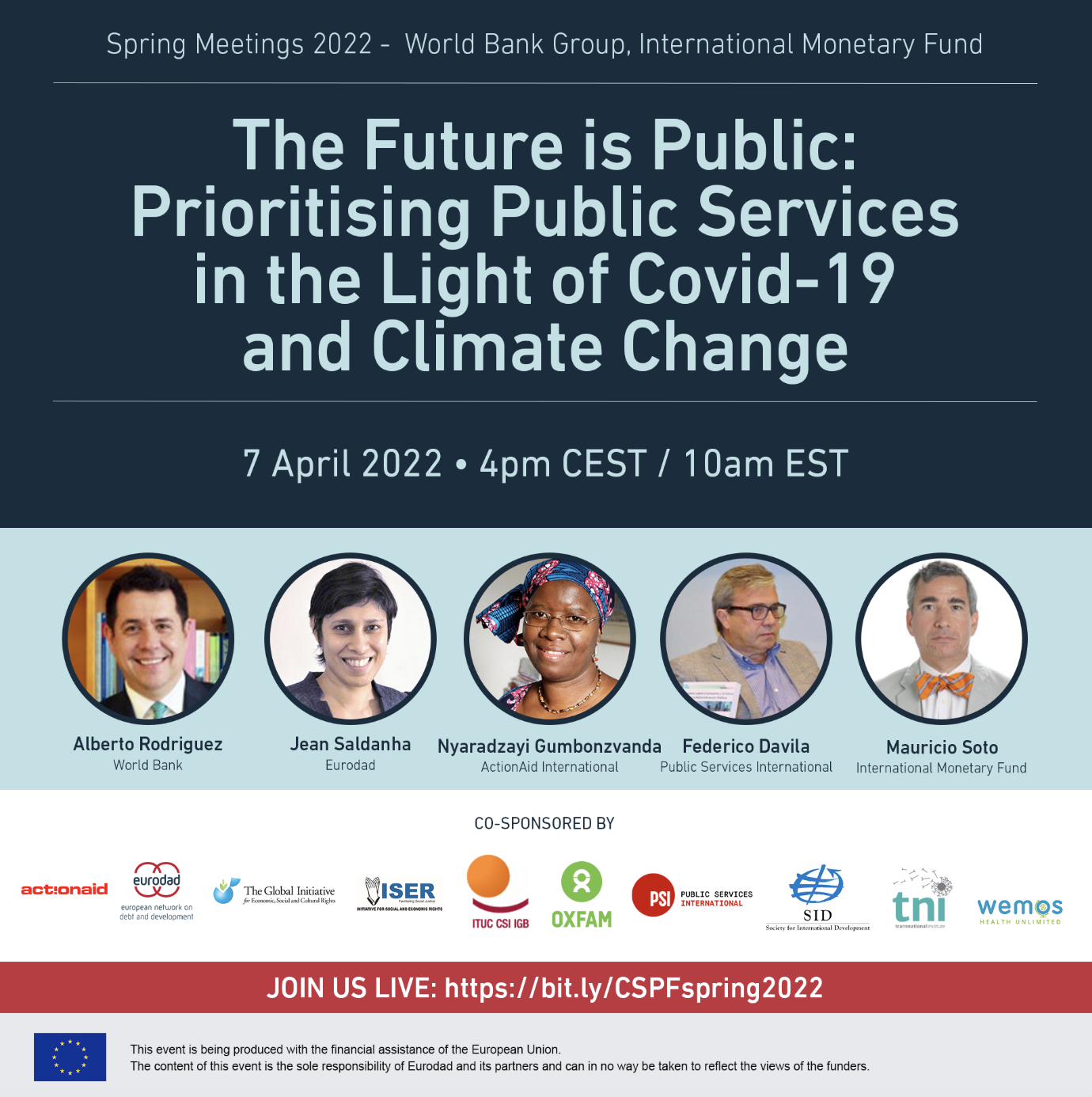

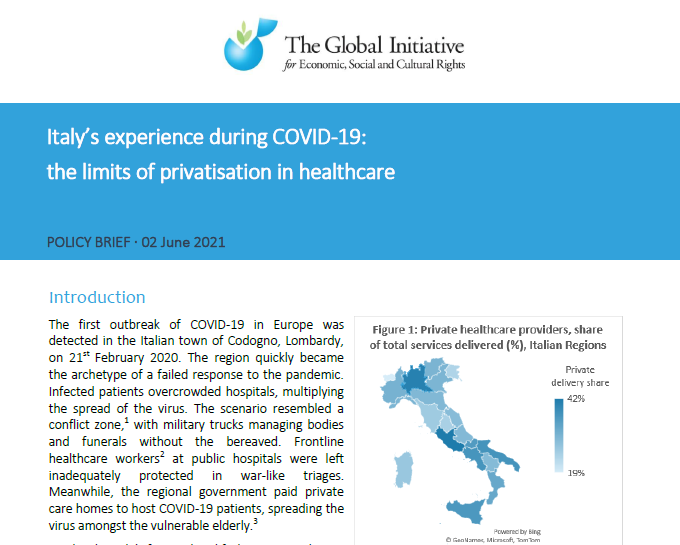

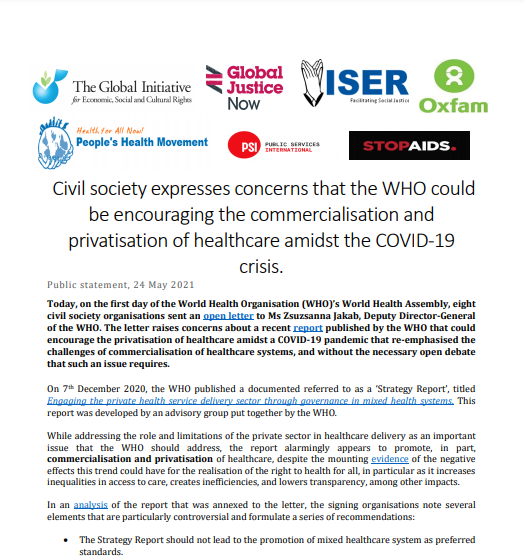

Recent decades have seen growing involvement of private actors in the provision of services which are critical to the enjoyment of economic and social rights such as education, healthcare and water. These are services which have traditionally been delivered by the State and considered ‘public’ (hereafter ‘public services’).

This growth of private involvement in public services that affect human rights is a phenomenon that can be described as privatisation.

The meaning of privatisation is multi-faceted.

+ Read More

Firstly, there are a variety of ways in which private actors can be involved. It may be through the private delivery of services, whether core services, for instance the private management of a health care facility or a school, or ancillary services, such as the provision of textbooks and medicine. It may equally be through increased privatisation of the financing of a sector, for instance by using public-private partnerships where a private actor takes part in the financing of the construction of a health facility. This is often referred to as financialisation. Privatisation in public services may also happen through subtle mechanisms, such as dynamics of privatisation in education. This consists of importing market approaches into the public sector, for instance using new public management techniques. The increase of market solutions, involving a competition between private actors seeking to maximise their benefits, for instance through encouraging land titling and competition between pastoralists, is generally described as marketisation. Closely related, commodification describes the increased treatment of a good or a service as a commodity, for instance by valuing and selling cultural places or practices. Service privatisation, financialization, and marketisation or commodification are inter-related and overlapping concepts, that in practice often occur concurrently. The term privatisation is used here to refer to all these phenomena.

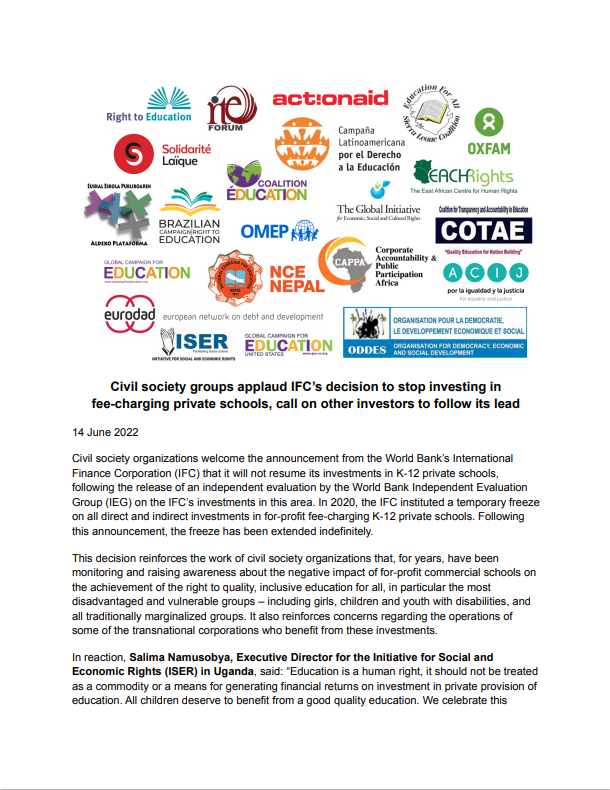

Secondly, there are a range of different actors that can be involved in the delivery of services. For example, services may be carried out by large-scale multinational for-profit companies, such as Veolia for water and Bridge International Academies for education, smaller enterprises at the national or local levels, and non-profit actors such as NGOs, faith-based organisations, and community-based organisations. Regarding financing, private actors may also include large philanthropic organisations, such as the Gates Foundation. When any of these actors adopts a market approach, whether they are formally for-profit or not, they are generally described as commercial actors - typically national or multinational corporations. Non-commercial actors may include community-based non-state actors, such as farmers’ cooperatives.

Our Approach

We aim to address how the these dynamics affect human rights, and what the human rights responses could look like. The diversity of the phenomenon makes it complex to apprehend. The different forms of privatisation and the diversity of the private actors involved require nuances in assessing its impact. There may be cases where privatisation can have a positive impact on human rights. However, privatisation of public services by commercial actors has raised many human rights concerns.

+ Read More

Concerns vary depending on the sector, and include economic discrimination and segregation, lower quality of, and access to, goods and services for marginalised groups, and the reinforcement of unbalanced power relations and unequal participation in the governance of economic, social and cultural spheres. A common feature is that they require the management and delivery of different sectors which affect human rights through mechanisms controlled by rights-holders on an equal basis, with a focus on the public interest. This is also sometimes described as the democratic governance or ownership of the economy. It may tentatively be referred to, from a human rights perspective, as the public delivery of rights: the organisation of the governance of goods and services controlled by the public/rights holders, for the public/common good. This provides an initial human rights analysis framework but demands more refinement.

Our work on privatisation is closely linked with our work on climate change. For example, privatisation can be a source of carbon emissions that drive the climate crisis, for instance by encouraging unsustainable large-scale farming or encouraging the use of schools or hospitals that are far away from users rather than local facilities. Both privatisation and the climate crisis are linked to inequalities. For instance, climate change will likely exacerbate inequalities and disproportionately adversely affect those who are already marginalised or disadvantaged. As in the case of our work on climate change, our approach is to look at the systemic discrimination suffered by groups, such as women, indigenous peoples, minorities, and people with disabilities. These groups are often disproportionately affected by the combination of inequalities, the climate crisis and privatisation. Collectively, these areas define an agenda to equalise power in the running of common services and activities to promote just transitions.

Theory of Change

Areas of Work

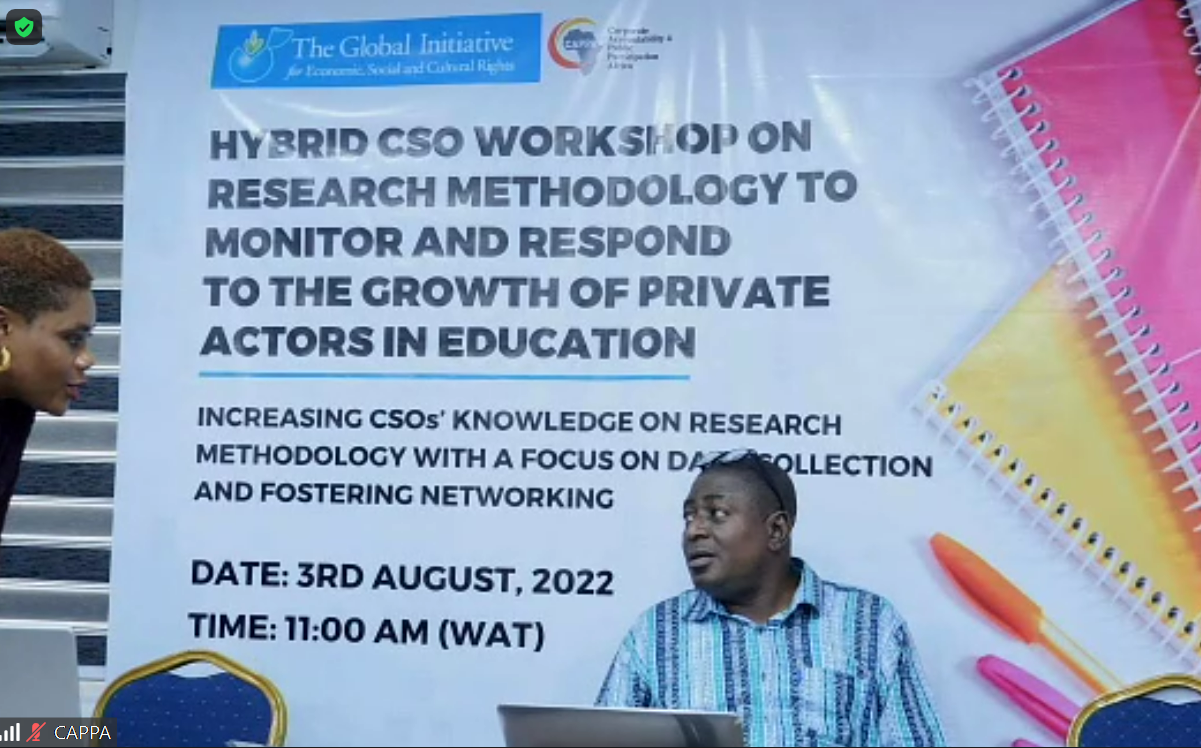

Education